Biologists have discovered a novel type of visual cell in deep-sea fish that challenges more than a century of scientific understanding about how vertebrates see. Researchers identified a “hybrid” photoreceptor that combines the physical shape of a rod with the genetic machinery of a cone. This unique adaptation allows specific fish species to see in the dim, gloomy twilight of the deep ocean where traditional eyes would struggle to function.

For decades, biology textbooks have taught that vertebrate vision relies on two distinct and separate cell types: rods for processing dim light and cones for detecting bright light and color. This new finding overturns that dogma, revealing that nature is far more flexible than previously thought. The discovery centers on the larvae of three deep-sea species found in the Red Sea, which have evolved a way to blend the best features of both cell types to survive in their extreme environment.

A Mix-and-Match Cellular Strategy

The study, published in the journal Science Advances, details how these fish break the standard rules of retinal development. Lead author Lily Fogg, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Helsinki, explained that the larvae utilize a “mix-and-match” strategy. The cells are shaped like rods—long and cylindrical to capture as many light particles as possible—but they operate using the molecular machinery typically found only in cones.

This combination creates a visual system perfectly tuned for the “twilight zone” of the ocean, located between 65 and 650 feet (20 to 200 meters) deep. In this blue-tinted darkness, neither pure rods nor pure cones function efficiently. By merging the sensitivity of a rod’s shape with the genetic programming of a cone, these fish bridge the gap, allowing them to spot predators and prey in conditions that would blind other creatures.

Different Paths for Different Species

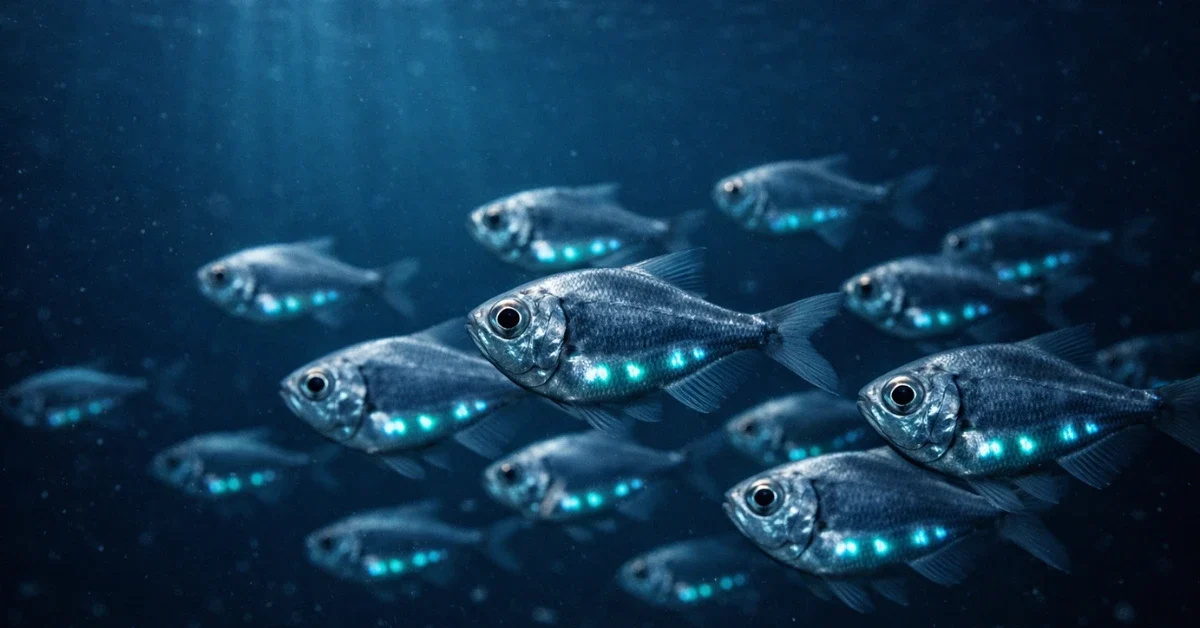

The research team examined three specific species: the hatchetfish (Maurolicus mucronatus), the lightfish (Vinciguerria mabahiss), and the lanternfish (Benthosema pterotum). While all three utilize these hybrid cells during their larval stage, their development diverges as they mature.

Most vertebrates follow a conserved path where retinas are dominated by cones early in life, with rods added later. However, the hatchetfish retains these unique hybrid cells throughout its entire lifespan. In contrast, the lightfish and lanternfish eventually transition to a more conventional visual system dominated by true rods as they grow into adults. This difference highlights an evolutionary flexibility that allows each species to optimize its vision for the specific light conditions it encounters at different life stages.

Rethinking Vertebrate Vision

The study suggests that the strict categorization of photoreceptors into “rods” and “cones” may be too rigid. Fabio Cortesi, a senior author and marine biologist at the University of Queensland, noted that this finding proves biology does not always fit into neat boxes. He added that he would not be surprised if similar hybrid cells are eventually found in other vertebrates, potentially even terrestrial species.

These fish also use bioluminescence—emitting blue-green light from organs on their bellies—to blend in with the faint sunlight from above, a strategy known as counterillumination. Their specialized vision likely plays a key role in regulating this camouflage, helping them hide from predators in the open water. This discovery provides compelling evidence that vertebrate eyes are highly adaptable, capable of rewriting their own genetic blueprints to conquer challenging environments.