A parasite hiding in the brains of around one in three people worldwide has a remarkable survival strategy, but scientists have uncovered how the human immune system fights back. Researchers at the University of Virginia School of Medicine discovered that immune cells possess a self-destruct mechanism that eliminates infected cells along with the parasite inside them, offering new hope for treating toxoplasmosis in vulnerable patients.

Toxoplasma gondii is a potentially dangerous parasite that infects warm-blooded animals and can spread throughout the body before settling in the brain, where it may remain for life. People most commonly encounter the parasite through contact with cats, contaminated fruits or vegetables, or undercooked meat. While roughly one third of the global population carries Toxoplasma, the majority never develop symptoms. However, when illness does occur in individuals with weakened immune systems, the consequences can be severe and potentially fatal.

Immune Cells Fight Back with Self-Destruction

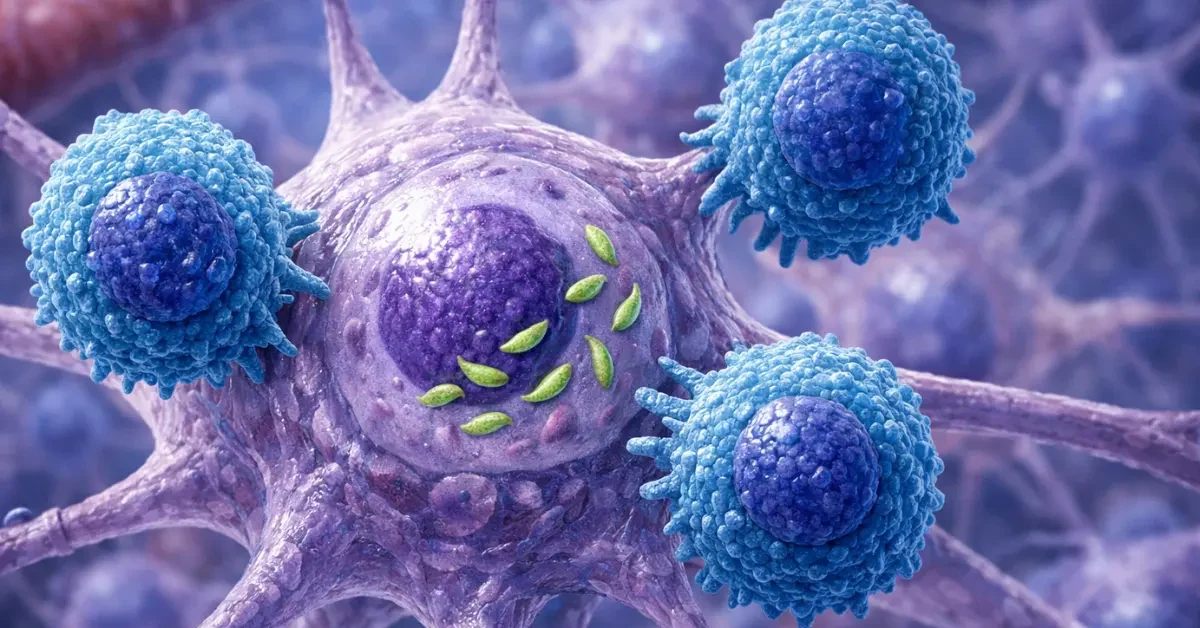

Led by Tajie Harris, director of the Center for Brain Immunology and Glia at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, researchers discovered that CD8+ T cells rely on a powerful enzyme called caspase-8 to control the parasite. These specialized immune cells are responsible for killing infected cells, but the parasite can actually invade the T cells themselves.

When Toxoplasma infects CD8+ T cells, those cells can trigger a self-destruct mechanism powered by caspase-8. Since the parasite needs to live inside cells to survive, the host cell dying means game over for the invader. Harris explained that understanding how the immune system fights Toxoplasma is crucial because people with compromised immune systems are particularly vulnerable to this infection.

Mouse Studies Reveal Critical Role of Enzyme

Laboratory experiments with mice demonstrated the importance of caspase-8 in controlling brain infections. Mice lacking caspase-8 in their T cells developed far higher levels of Toxoplasma in their brains compared to mice whose T cells produced the enzyme, even though both groups mounted strong immune responses against the infection.

The difference in outcomes was striking. Mice with caspase-8 remained healthy, while those without it became severely ill and died. Examination of brain tissue showed that CD8+ T cells in mice lacking the enzyme were much more likely to be infected by the parasite.

Why Parasites Rarely Infect T Cells

The research team scoured scientific literature to find examples of pathogens infecting T cells and found very few cases. Harris noted that they now understand why caspase-8 leads to T cell death, and the only pathogens that can survive in CD8+ T cells have developed ways to interfere with caspase-8 function. Before this study, researchers had no idea that caspase-8 was so important for protecting the brain from Toxoplasma.

These findings add to growing evidence that this enzyme plays a broadly important role in helping the body control infectious threats. The discovery provides a better understanding of why and how vulnerable patients can be helped in fighting this infection.

Separate Research Targets Parasite Protein

In parallel research at the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine, parasitologist Rajshekhar Gaji and his team identified a different approach to fighting the parasite. They discovered that switching off a single protein inside Toxoplasma called TgAP2X-7 can kill it. This protein appears essential to the parasite’s ability to invade hosts, form plaques, and self-replicate.

When researchers genetically modified parasites to degrade their TgAP2X-7 proteins, the parasites couldn’t form plaques and their invasion success rate dropped from nearly one hundred percent to below fifty percent. They also struggled to replicate. Best of all, this protein bears no similarities to anything in the human body, which means there’s potential to target it without harming patients.

Growing Health Concern

Toxoplasmosis is most serious in individuals with weakened immune systems, including those with cancer, HIV, or who are taking immunosuppressants. Without a healthy immune system to keep the parasite at bay, these patients can quickly develop toxoplasmosis, which brings flu-like symptoms, swollen lymph nodes, and brain inflammation. The parasite can also be transmitted to a developing fetus during pregnancy, potentially causing developmental problems and even miscarriages.

Current treatments for acute toxoplasmosis involve medications that target mechanisms in the parasite that are biologically similar to processes in human bodies. This often puts patients at risk of severe side effects, restricting treatments to situations where infections are considered dire.

The University of Virginia research was published in the journal Science Advances and funded by the National Institutes of Health along with several University of Virginia awards. The findings could lead to new therapeutic approaches for one of the most common parasitic infections affecting humans worldwide.