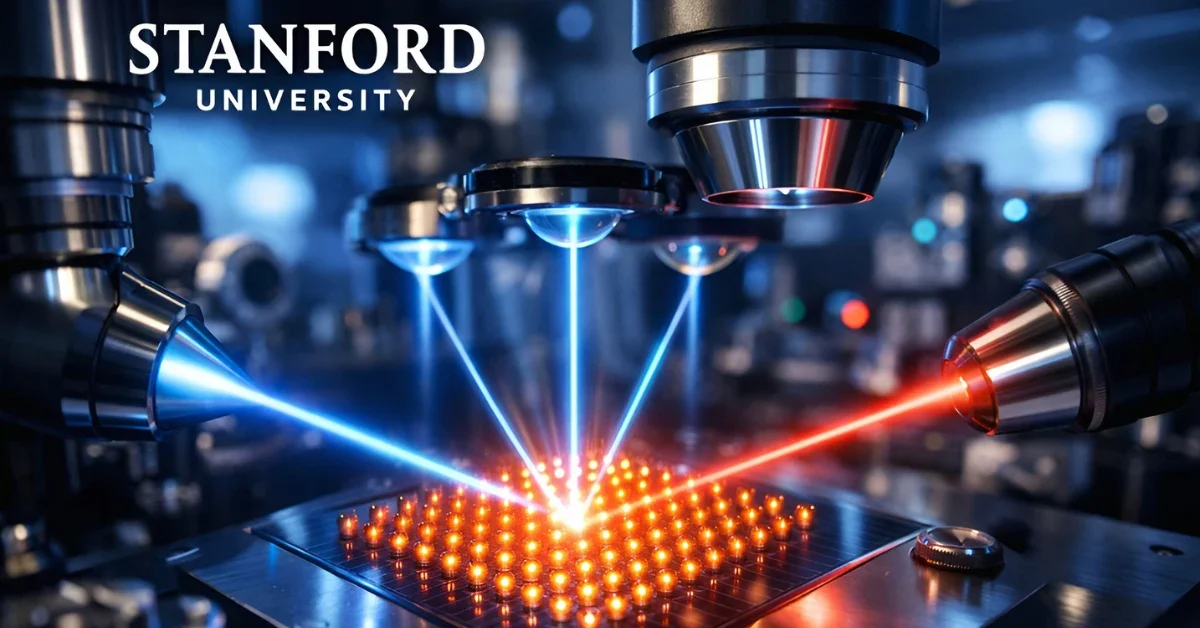

Stanford physicists have introduced a novel optical cavity array system that speeds up qubit readout in quantum computers. This breakthrough tackles a key scaling challenge by linking each atom qubit to its own dedicated cavity for parallel light collection. A new study in Nature details a 40-cavity array with individual atoms and a prototype surpassing 500 cavities, pointing toward systems with millions of qubits.

The platform, called a cavity-array microscope, merges neutral-atom arrays with optical cavity quantum electrodynamics. It enables fast, non-destructive measurement of single atoms across a two-dimensional setup. Researchers demonstrated parallel readout on millisecond timescales, including via a fiber array for networking tests.

Qubit Readout Challenge Solved

Quantum computers rely on qubits from atom quantum states, which can hold zero, one, or both values simultaneously. This superposition promises to slash computation times for tough problems from millennia to hours. Yet reading qubit states quickly has proven tricky.

Atoms emit photons slowly and scatter them everywhere. Past efforts paired whole atom arrays with one shared cavity mode, limiting addressability and growth. The Stanford design changes that. Each atom now sits in its own cavity, achieving strong light-matter coupling without nanophotonics.

Jonathan Simon, senior author and associate professor of physics and applied physics at Stanford, explained the issue clearly. Atoms fail to emit light fast enough at scale, and it spreads in all directions. Optical cavities direct that light efficiently, and this setup gives every atom its personal cavity.

Innovative Cavity Design

Optical cavities trap light between reflective surfaces, bouncing it repeatedly for stronger atom interactions. The team added microlenses inside each cavity. These focus beams tightly on single atoms at micrometer scales, matching optical tweezer spacings.

The macro-scale resonator spans about 34 centimeters. An microlens array stabilizes beams and demagnifies them at the atom plane. This yields peak cooperativity above unity, with low crosstalk under 1% between neighboring modes.

Atoms stay distant from dielectric surfaces, easing engineering. The result: homogeneous coupling across the array. Adam Shaw, first author and Stanford Science Fellow, described the shift. The architecture goes beyond basic mirrors, promising quicker distributed quantum machines with high data rates.

Scalability Demonstrated

The study showcased a working 40-mode array. A next-generation version boasts over 500 cavities and nearly ten times better finesse. Goals include tens of thousands of cavities soon.

This supports linking quantum processors into networks. Imagine quantum data centers where machines connect via cavity interfaces, forming supercomputers. Fiber-coupled readout proves the modular approach works.

Simon likened classical computing to sequential searches. Quantum systems compare answer combos like noise-canceling headphones, boosting correct ones while damping errors.

Broad Applications Ahead

Millions of qubits will outpace top supercomputers. Fields like materials design, chemical synthesis for drugs, and cryptography stand to gain. Cavity arrays also boost biosensing and microscopy for medical advances.

In astronomy, they could sharpen optical telescopes to spot exoplanets directly. Shaw sees single-particle light control reshaping how we view the world.

Co-authors include David Schuster from Stanford, plus experts from Stony Brook University, University of Chicago, Harvard University, and Montana State University. Doctoral students Anna Soper, Danial Shadmany, and Da-Yeon Koh contributed from Stanford.

Support came from the National Science Foundation, Air Force Office of Scientific Research, Army Research Office, Hertz Foundation, and U.S. Department of Energy. Some researchers consult for Atom Computing and hold stock options there. Shadmany, Jaffe, Schuster, Simon, and Stony Brook’s Aishwarya Kumar share a patent on the resonator geometry.

This platform unlocks many-cavity quantum electrodynamics. It pioneers large-scale quantum networks with atom arrays, blending high-fidelity logic from arrays and strong coupling from cavities.

The work promises hybrid atom-photon systems for faster measurements and engineered Hamiltonians. Engineering hurdles linger, but the foundation feels solid for quantum leaps forward.