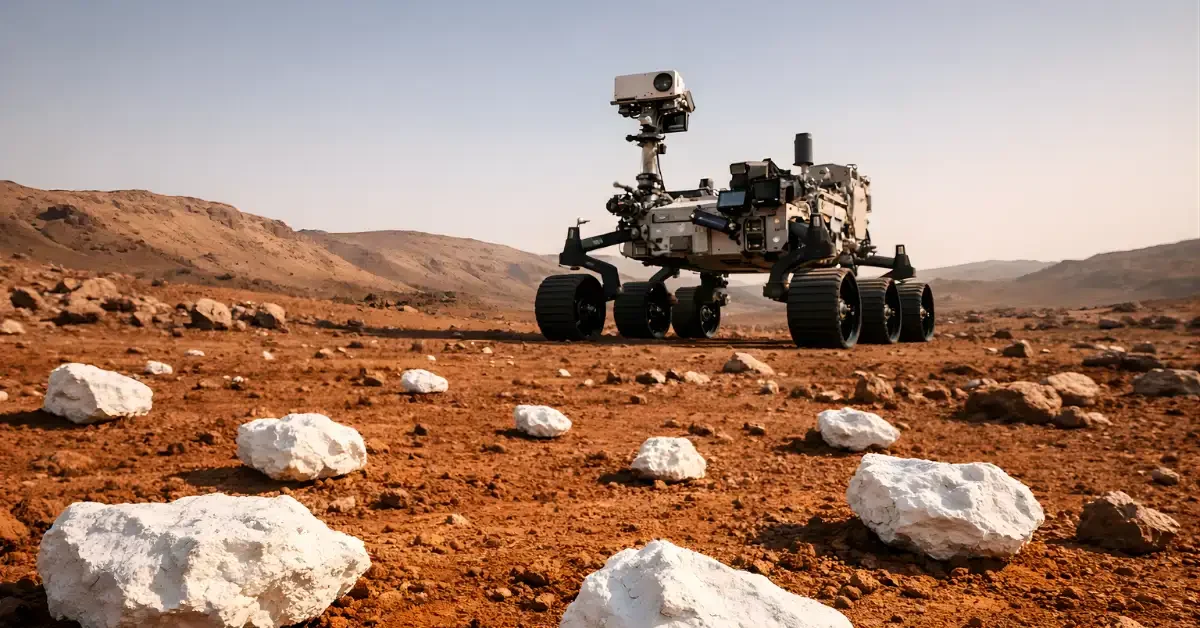

Small, pale “white rocks on Mars” spotted by NASA’s Perseverance rover are giving scientists a fresh clue that parts of the Red Planet may have once been warm, wet, and rainy for a very long time.

Researchers say the light-colored fragments in Jezero Crater are kaolinite, a white, aluminum-rich clay that on Earth typically forms only after rocks are heavily altered by lots of freshwater over long periods—often linked to warm, humid climates and heavy rainfall.

The work was published in the journal Communications Earth & Environment and is led by Adrian Broz, a Purdue University postdoctoral research associate, working with Briony Horgan, a long-term planner on the Perseverance mission and a professor of planetary science at Purdue University.

Why these white rocks matter

Perseverance identified the pale rocks as kaolinite clay, which stands out against Mars’ reddish-orange surface and suggests some areas may once have supported “wet oases” with humid conditions and heavy rainfall comparable to tropical climates on Earth.

On Earth, kaolinite forms after other minerals are leached away from rocks and sediments through prolonged exposure to water, a process that can require millions of years of persistent rainfall in warm, wet environments.

Horgan said, “You need so much water that we think these could be evidence of an ancient warmer and wetter climate where there was rain falling for millions of years.”

What Perseverance found in Jezero Crater

The kaolinite fragments range from small pebbles to large boulders, and they appear scattered along Perseverance’s path in Jezero Crater.

Perseverance has been traveling in Jezero since landing there in February 2021, and scientists say the crater once held a lake about twice the size (or area) of Lake Tahoe.

Early checks used the rover’s SuperCam and Mastcam-Z instruments to examine the rocks and compare them with kaolinite and related materials found on Earth.

A mystery: Where did the rocks come from?

Even with the strong kaolinite signal, the origin of these white fragments is still unclear because the rover has not found a major nearby outcrop that clearly produced them.

Horgan described the puzzle directly: “They’re clearly recording an incredible water event, but where did they come from?”

Scientists have floated more than one idea for how the pieces ended up scattered across the crater floor, including being washed into Jezero’s ancient lake by the river that formed the delta, or being thrown in by an impact and scattered.

Researchers also note that satellite or orbital data have identified larger kaolinite deposits elsewhere on Mars, but Perseverance has not reached those sites.

Testing rain vs. hot water explanations

To strengthen the case, Broz compared Perseverance’s observations of Martian kaolinite with Earth samples from near San Diego, California, and from South Africa, and the reports say the match was close.

Kaolinite can form in more than one way on Earth, including in hydrothermal systems where hot water alters rock, so the team also evaluated whether hot-water alteration could explain the Martian fragments.

The sources describe a key difference: hydrothermal processes can leave a different chemical signature than lower-temperature leaching driven by rain over long periods, and comparisons using multiple datasets favored rainfall-driven weathering as the better fit for these Mars rocks.

Broz emphasized why this matters for understanding Mars today: “So when you see kaolinite on a place like Mars, where it’s barren, cold and with certainly no liquid water at the surface, it tells us that there was once a lot more water than there is today.”

What it could mean for habitability

Scientists describe kaolinite and similar clays as a kind of geological record that can preserve clues about environmental conditions from billions of years ago.

The discovery adds to the wider debate over ancient Mars—whether the planet’s early wet periods were brief or whether some regions stayed warm and humid long enough to cause major, long-term chemical weathering.

Broz tied the finding to the basic requirement for life as we know it, saying, “All life uses water,” and adding that a rainfall-driven environment would be “a really incredible, habitable place where life could have thrived if it were ever on Mars.”